At the front lines of this pandemic are healthcare workers – exhausted, covered in bruises from hours of wearing protective gear, and worried about bringing the virus home to their loved ones. Day in and day out, they put themselves at risk to save others, but the risk isn’t just physical. For many doctors, nurses, and first responders, the pandemic has taken a tremendous psychological toll. It is no longer the virus itself killing these front-line heroes, but also suicide.

Just last month, New York City lost two heroes to the mental health impact of COVID-19: Dr. Lorna Been, who was so committed to her job that she returned to work after recovering from the virus, and John Mondello, a young emergency medical technician for the New York City Fire Department. Their tragic suicides highlight the importance of prioritizing mental health, now more than ever.

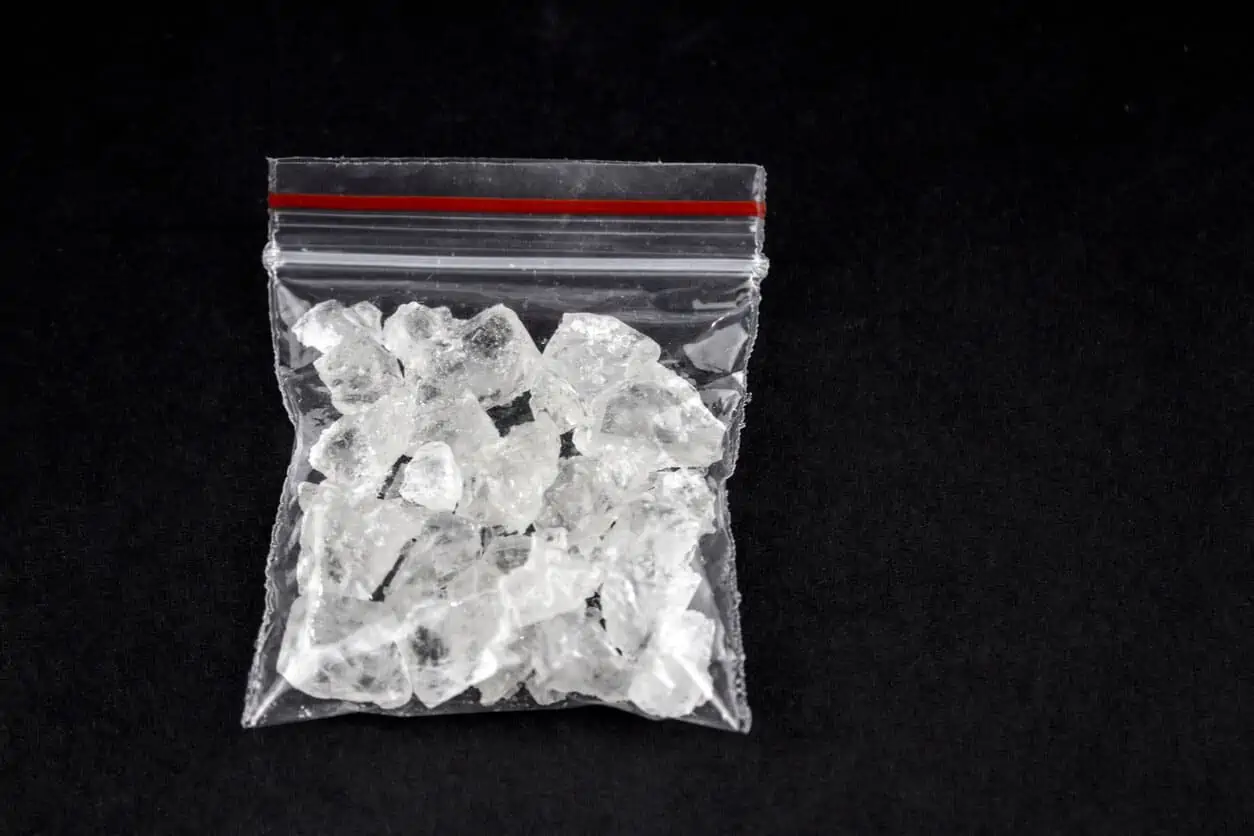

Clinical psychologist Curtis Reisinger believes the pandemic has created secondary victims in providers who experience trauma related to a patient’s care. While devastating, the emotional distress currently being experienced by healthcare workers is not surprising. Even before the pandemic, data showed that those in medical-related professions had a high suicide risk. In 2015, healthcare practitioners had the sixth (among women) and eighth (among men) highest suicide rate. Substance abuse was also a concern in the field, with roughly 10 percent of medical professionals struggling with drugs and alcohol. But the higher than normal stress levels and constant exposure to death caused by coronavirus is exacerbating the challenging conditions of an already demanding job, creating an even greater threat for healthcare workers.

A recently published study that surveyed healthcare workers in China, where the outbreak is believed to have originated, revealed just how much mental health has been. The study reported that 50 percent of participants experienced depressive symptoms, 45 percent experienced anxiety, 34 percent experienced insomnia, and 72 percent experienced distress.

“They’re working really long hours, they’re seeing these traumas that are burning into their minds, and they have very limited time to release,” says Dr. Shauna Springer, a licensed psychologist and trauma-recovery expert. Practicing self-care and taking a moment to process the trauma is key for maintaining good mental health, but doing so is particularly difficult in the middle of a pandemic. “You tear up, but you can’t cry. You tell yourself, cry later,” shares Laura McKee, a nurse who left her job in Florida to volunteer in New York City, the epicenter of the crisis.

Separated from their loved ones and too busy to slow down, those at the front lines rarely receive the assistance they need. Health officials both expect and fear an increase in the number of PTSD cases among healthcare workers in the coming months. To support healthcare professionals, states are making resources more readily available by offering free support lines and providing free mental health services. Private companies such as CVS have also pledged to help flatten what they are calling “the second curve – the less visible but escalating mental health crisis resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic.” According to Christine Moutier, chief medical officer for the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, it is important to act now. “We know suicide is preventable,” she says, adding that access to therapy and early mental health screenings are key in combating the mental health crisis that awaits.

If you or someone you know needs help, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK (8255) or text the Crisis Text Line at 741741.

If you or a loved one is struggling with addiction, Mountainside can help.

Click here or call (888) 833-4676 to speak with one of our addiction treatment experts.

By

By